Sunday, February 27, 2011

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) Directed by Stanley Kubrick

Astrid:I am tickled by the idea that intelligent life form from another planet turns out to be a boring black obelisk resembling a tomb stone. It does not relate to our experience of the animate. Stone is inanimate, soulless, and expressionless here on earth. 2001 A Space Odyssey is full of such subtle but shattering moments of imagination. It has also become a kind of visual bible of how we are used to imagining the space out there.

Ultimately, this movie is trying to grapple the question where are we and what are we in relation to everything. That's a little too much to take on I fear – and yet, I'm glad some of us keep asking that question and acting to find answers. In the context of cinema, I am happy to witness an approach to narrative and plot, which still seems revolutionary and challenging. The lack of resolve and human interest in a 3-hour-piece makes me liken the film to a classical concert or possibly opera. The result was that I was often bored and willing to give up on it all.

The use of classical music and human voice in 2001 is astonishing. While I am staring into the vast emptiness of the space, I hear the disturbing mesh of a mixed choir and it acts as a connection to humanity – the audience. Much of the drama comes from music, while the visuals alone would not guide us to the same emotions. Of course, silence has an even greater part in the film. It is powerful and can stretch the experience of time. The whole movie speaks in the language of dissociation and hallucination. I will probably never feel like watching this one again.

Nick:

Here we are in 2011, ten years after the events depicted in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Some of the ideas and progress shown in the picture have come to be true. An over-reliance on computers. Communication has reached the same level that 2001 imagined in 1968. Looking at the space ship interiors as featured here, the film's influence on design is still apparent now. But theories on evolution and our origins still divide most of the world. Although space stations and various space programs exists, an ambition to discover and venture to other planets is sadly curtailed. This aspect of 2001 has not come to fruition. Our capacity for human error though, is a constant.

Stanley Kubrick makes claims, after Arthur C. Clarke whose book this is based on, that the evolution of man was prompted (or encouraged, perhaps) by some artificial artifact (a black obelisk). In my view, this is as credible as any other theory proffered about our evolution. The early scenes of primates territorial rights establishes a key behavioral pattern that still dominates the way we behave today. But once the picture moves into space, other than offering us a psychotic computer (Hal), the picture refuses to give any other great notions. It becomes a slow burning thriller, based on one's man's endless, lonely journey to Jupiter and beyond.

I'm not such a Kubrick fan. I admire more than love his films. 2001: A Space Odyssey represents the peak of Kubrick's fascination with cold surfaces, be they human or in space. This is as radical a picture as any mainstream director has offered. There is no reliance on narrative or performance for that matter. Here we can just marvel at what we see on screen, from the spaceship design to the barren earth, through to the colorful shards of light that dominate the screen in the latter part. I'm not sure this means anything. This picture didn't say anything to me. But the visual atmosphere created by Kubrick aligned with his use of music by the two Strauss' (Johan & Richard) creates a creepy intensity that is fascinating.

Monday, February 14, 2011

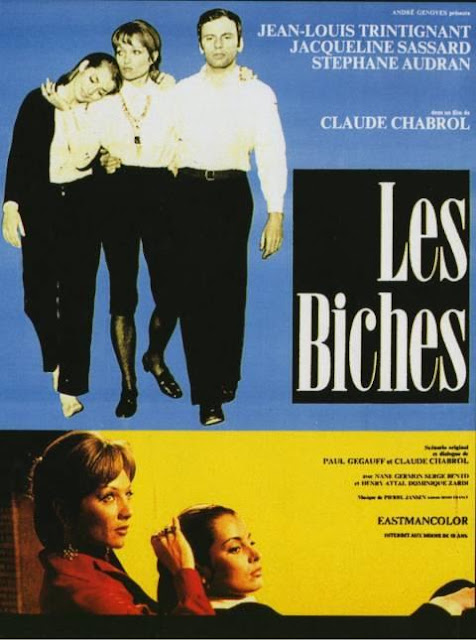

Les Biches (1968) Directed by Claude Chabrol

Astrid:

Have you noticed how cuteness has become something to aspire to? Being cute has been a quality reserved for children and baby animals, something denoting innocence, softness, child-like. But these days adult women are demanding their right to remain cute – or to use cuteness. There are new connotations for cuteness, which can now relate to a certain pink and fuzzy sexiness too. I have noticed and felt the pull of cute.

Before watching Les Biches I assumed the title meant The Bitches. Pardon my non-existent French.

After seeing the film I realized its English title is The Does. Does are female deer. Cute little cuddly things with hoofs. I must add that if I had to tell you what animal I would describe myself as, I would have to pick a deer/doe. But not Bambi.

Why the two women in Les Biches deserve to be aligned with such mystical animals as deer, I don't know. This is a movie about attraction to someone in such an extreme way that it isn't enough to love them, you must become them. There is much left unclear, much unexpressed emotion of hatred and passion. There is beauty to look at, and there is a lesbian love story to be read. There is also a battle between the cute and the regally adult forms of feminine sensuality. Go watch it on a vacuous spring evening!

Nick:

I'm open to suggestions of vagueness. I'm open to empty thoughts and vacuous digressions. I'm into gestures that don't mean anything. I'm into space as art. I'm into nothing ever happening but still feeling special. I appreciate a statement of silence. It's all in the Mise-en-scène. I can dig you brother if you can spare me a dime?

Can you imagine going through life and always being referred to as some other countries Alfred Hitchcock? For Claude Chabrol this seems to be the case. It's even printed on the box that the 8 (!) movie collection of his work came with..."The French Hitchcock". Like the real master of suspense Hitchcock, it says here that Cabrol is also the master of suspense. How many can go round being masters of suspense? But Chabrol is in reality far harder to pin down. He fills Les Biches with atmosphere, raises tension and even suspense at times, but it's all topped off with a weary shrug of the shoulders. Elegance rarely appears like this on screen.

Lesbian lovers, betrayal and Jean-Luis Trintignant is enough to wet one's appetite. Looking forward to the other seven.

Have you noticed how cuteness has become something to aspire to? Being cute has been a quality reserved for children and baby animals, something denoting innocence, softness, child-like. But these days adult women are demanding their right to remain cute – or to use cuteness. There are new connotations for cuteness, which can now relate to a certain pink and fuzzy sexiness too. I have noticed and felt the pull of cute.

Before watching Les Biches I assumed the title meant The Bitches. Pardon my non-existent French.

After seeing the film I realized its English title is The Does. Does are female deer. Cute little cuddly things with hoofs. I must add that if I had to tell you what animal I would describe myself as, I would have to pick a deer/doe. But not Bambi.

Why the two women in Les Biches deserve to be aligned with such mystical animals as deer, I don't know. This is a movie about attraction to someone in such an extreme way that it isn't enough to love them, you must become them. There is much left unclear, much unexpressed emotion of hatred and passion. There is beauty to look at, and there is a lesbian love story to be read. There is also a battle between the cute and the regally adult forms of feminine sensuality. Go watch it on a vacuous spring evening!

Nick:

I'm open to suggestions of vagueness. I'm open to empty thoughts and vacuous digressions. I'm into gestures that don't mean anything. I'm into space as art. I'm into nothing ever happening but still feeling special. I appreciate a statement of silence. It's all in the Mise-en-scène. I can dig you brother if you can spare me a dime?

Can you imagine going through life and always being referred to as some other countries Alfred Hitchcock? For Claude Chabrol this seems to be the case. It's even printed on the box that the 8 (!) movie collection of his work came with..."The French Hitchcock". Like the real master of suspense Hitchcock, it says here that Cabrol is also the master of suspense. How many can go round being masters of suspense? But Chabrol is in reality far harder to pin down. He fills Les Biches with atmosphere, raises tension and even suspense at times, but it's all topped off with a weary shrug of the shoulders. Elegance rarely appears like this on screen.

Lesbian lovers, betrayal and Jean-Luis Trintignant is enough to wet one's appetite. Looking forward to the other seven.

Friday, February 11, 2011

Ryan's Daughter (1970) Directed by David Lean

Nick:

Critical consensus in a positive light is something we all strive for in all walks of life. We all want our friends to appreciate us and our peers to accept us. It is churlish to think otherwise. Yet, at times we all encounter situations where our actions do not meet the approval we would like. Working in the field of music all of my life, it's been interesting to see how the critical community works from different perspectives. In recent years, there seems to be a critical view that artists should take on board general critical responses to their work. I don't accept this. However much I appreciate some critical commentators, I don't need them informing my creativity at all. Yet, I think about this blog and often I can be found dishing out scathing commentary. I wonder if a unanimous rejection of someone's efforts can force them to stop all together? This certainly seems to be the case for David Lean and his film Ryan's Daughter.

The critical reaction to Ryan's Daughter at the time of its release seems to have been universal ridicule, which hurt Lean so much he went into a hiatus from making pictures for many years, actually only making one more film in the 1980's. Is Ryan's Daughter that bad? Ryan's Daughter is certainly a film out of time, its classical storytelling and slow pace, almost fantasy like imagery is in stark contrast to a more realist film making that was prevalent at the end of the 1960's and early 1970's. Yes, this film is old-fashioned. Historically, as in many of Lean's epic pictures of this time (Doctor Zhivago, Lawrence of Arabia), any accuracy is pretty much forsaken. Set in a small Irish village just before the 1916 Easter Rising, this is a rather cliched picture of the fledgling IRA and the depiction of the Irish people seems very patronizing. The British are crudely portrayed as imperialist swine. As The Troubles raged in 1970, Ryan's Daughter simplified version of these earlier events must have seemed very quaint.

But if you were to forgive these problems with the film, there is much to admire. Lean never lost his eye for a great scene or framed composition. Ireland has surely never looked this good on film, in fact, few films have looked this good. Period. You could just watch this with no audio and be blown away by what you see. Is this not the pure essence of cinema? But in silence, you'd be missing out on one of Maurice Jarre's best scores. Or, you would miss the subtlety of Robert Mitchum's performance. Very much cast against type, it is worth revisiting Ryan's Daughter alone for Mitchum's much maligned turn as Charles Shaughnessy. Throw in a sensual role for Sarah Miles as the sexually hungry Rosy Ryan, whose indiscretions are the real heart of this picture, and real substance appears. Trevor Howard is effortlessly great as the stern Catholic priest of the village. Ryan's Daughter is a much better film than Doctor Zhivago, and not far from the great heights of Lean's best picture Lawrence Of Arabia. David Lean still understood the power of cinema when he made this film. It was to take you somewhere you had never been before and show you something through his own vision. In this respect, Ryan's Daughter is ripe for re-discovery.

Astrid:

I used to be a Breaking The Waves -girl, as I mentioned in our review. Had I been born in another decade I might have been a Ryan's Daughter fan as devotedly. It is clear that Lars Von Trier has been immersed in the story of Ryan's Daughter and the film's aesthetic – so much of it Trier borrowed for Breaking The Waves.

I am learning to appreciate cinematography as a potent tool for narrating through the depiction of landscapes. Nature and its large and small features, weather conditions, light; these can add emotion to narrative. In fact they can be the emotion. Where people are reserved, nature seems to often act dramatic and over-powering. Ryan's Daughter portrays such a romantic Irish coastline full of nature's contradictions that I found myself wishing to live there.

Yet, the film depicts the small village as a place of control and of great suspicion towards newcomers.

The church rules over the population with one drunk priest. But where his eye does not see, there is hatred, jealousy, poverty and meanness.

As long as I am talking about something else than desire and pleasure here, I am derailing from what matters in Ryan's Daughter. It is a portrait of a young woman finding her sexual drive and need. Her quest is both socially accepted (in the form of marriage) and denied (her affair to an English soldier on a break from the front lines of the WWI). The contradiction is the crux.

Ignorance and innocence mixed with a desire for pleasure has long been a certified cocktail of trouble for women. It also makes for good movies.

Tuesday, February 8, 2011

To Have and Have Not (1944) Directed by Howard Hawks

Astrid:

Today I am going to write about me, Bacall and my love relationships. Lets begin with fashion. My new clothes arrived from Paris today – yes, just before I ran out of money, I ordered skirts and pants through mail order and hoped for the best. The result: Perfect fit. This relates to the film under review, because I imagined Bacall's über-elegance to be of the French variety. It also relates because I made my choice for new garments with the hope of purchasing a little bit of sassiness. A boost of it.

Lauren Bacall is the queen of sassy. To Have and Have Not marks her entry into the world of cinema at the ripe age of 19, and what an impressive entry it is. She steals, barks, sings, and moves her hips to the music. She also smokes, lights matches and, importantly, delivers impeccable lines of abstract wit.

It is not surprising that Bogey acting opposite her, simply melted and fell in love (also in real life).

Bogart and Bacall had 16 years between them – it's the usual Hollywood age gap for a good healthy relationship! Having tested it myself, I can tell you it also works outside of Hollywood. Forget about Casablanca and the clean sweet mystery of Ingrid Bergman. Slim (Bacall) will talk dirty and still leave Martinique with you in the end.

Just so you can also be 'bitten by a dead bee': you need to watch and hear Hoagy Carmichael singing his song "Hong King Blues" in the middle of To Have and Have Not. Don't you think he adds yet another layer of cool to the film.

Anyway, here's my final word: I may be poor, but my French skirt fits.

Nick:

What a woman Nancy 'Slim' Hawks (pictured below) must have been. An excellent article by David Thomson in this month's Sight and Sound tells us that Hawks' wife was the inspiration for Lauren Bacall's turn as ....you guessed it, Slim in To Have And Have Not. Not only this, but Bacall's clothes in the picture were like the real Slims' and some of the dialogue Bacall spoke came straight from Hawks' wife. Her marriage to Hawks sparked a new kind of woman character in Hawks' films: intelligent, independent and purring sexuality.

Based on Earnest Hemingway's book, To Have And Have Not radically changed for the screen with Bacall's Slim not even appearing in the original book. Hemingway must have felt pacified when he had a brief affair with the real Slim Hawks. But what still serves the film best is the interplay between Bacall, only 19 in her debut feature and the leading man Humphrey Bogart. The onscreen chemistry would lead to Bogart and Bacall becoming real life lovers. The verbals are sharp, witty and filthy and it's what separates and improves on what is basically a re-write of Bogart's previous Casablanca. The plot is not so important, the sexual foreplay is everything.

Hawks' reputation is as one of the great directors of his time who could try his hand at anything. Gangsters in Scarface, romantic comedy in Bringing Up Baby, Noir in The Big Sleep and The Western in Red River to name but a few. The Bogart-Bacall love in would reach even higher sexual tension with The Big Sleep. But as I close my eyes and listen to Hoagy Charmichael's songs, I recall Bacall asking Bogart if he can whistle, my own love affair with the cinema is brought into clarifying euphoria.

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

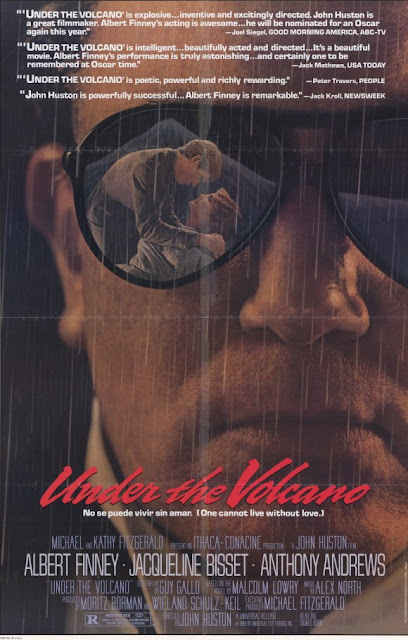

Under the Volcano (1984) Directed by John Huston

Nick:

Moving to Finland 12 years ago was quite a culture shock for me. Not in the sense that it was some culture free zone, but in respect to the culture of drinking. I come from England where heavy drinking from an early age or going to the pub every night is almost a birth right. Finnish drinking just operates at a different level. Social drinking was a ticket to get to know many people in a short time. I've always been a very slow drinker and not one to indulge too much in the art. But my first year in Finland was very much a drunken haze. I quickly moved on from this just to adapt to my new situation. Still, in my capacity as a record producer for a zillion young bands over the years, alcohol has been a constant accessory to many artists. A certain level of alcoholic incapacity is accepted in Finland, it's a normal part of the fabric of life. Or that's the way it seems to me. I'm only telling this because Albert Finney's portrayal of alcoholic diplomat Geoffrey Firmin in Under The Volcano is behavior I've witnessed at various times over the years (and not exclusive to Finland I may add).

Finney's turn could be the best drunk on screen I've seen. John Huston was near the end of an amazing directorial career. His trademark slow pace, rich character and dry dialogue are all present here. There is some back story: Under The Volcano is set in one day in Southern Mexico just before the outbreak of the Second World War. Firmin lives with his half brother Hugh (Anthony Andrews in a very Dirk Bogarde like performance), slowly drinking himself to death. His wife Yvonne (stiffly played by Jacqueline Bisset) returns from America to save their marriage. The trio venture out for the day, Firmin increasing his alcohol intake as the trip progresses, raging at all and sundry, fading in and out of focus. He has no interest in saving his marriage (after an affair between Hugh and Yvonne), he cares not for the coming war, the local political unrest, he just wants to drown in self pity and the bottle.

Under The Volcano is grim, but Finney is electric. The last half an hour set in a remote Mexican whore house is disturbing and harrowing viewing. It twists the knife and is uncomfortable to watch. The Mexico of this time is viewed as surreal and nightmare like. Finney is as brave as anyone for taking this role. Huston spells it out: You just can't help people if they don't want it, even if tragedy is apparent. The saddest thing? I've known people this fucked up by the juice.

Astrid:

It seems that movies are as in love with alcoholics as everyone else. Contradictions are forever fascinating and what condition would be better in illustrating the claim than a staggering diplomat alcoholic?

Under The Volcano is set in Mexico at the very Eve of the Second World War. Mexico acts as a strangely beautiful and rich backdrop to a complete descent into deadly depression. The political climate, or Firmin's (Albert Finney) post as a diplomat do not matter in the story actually. It is the portrayal of the alcoholism that ultimately makes the film claustrophobic and gives it its power. It's a close-up on a death wish.

Firmin drinks to get sober and to get drunk. He drinks bottles of liquor as if they were water. Sobriety has become a foreign state to him, much like his home country and his loved ones. He is well past hiding his drinking and his wife has left. The only one left is his half-brother (Anthony Andrews), who was having an affair with Yvonne, the wife, before she took off.

Despite these facts, Yvonne comes back to her husband. She believes in a new beginning, even if she doesn't believe her husband will be sober in it. These dreams are soon destroyed as the reality unveils in front of her hopeful eyes.

Is it the alcohol that kills them, or is it coincidence? I have rarely found such a realistic and unflattering depiction of alcoholism in films, where characters can usually down unfathomable amounts of booze without concern. Unlike in Leaving Las Vegas, there is no glamor or romance attached to Under The Volcano. Everything is lost. The ending is a little too abrupt still.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)